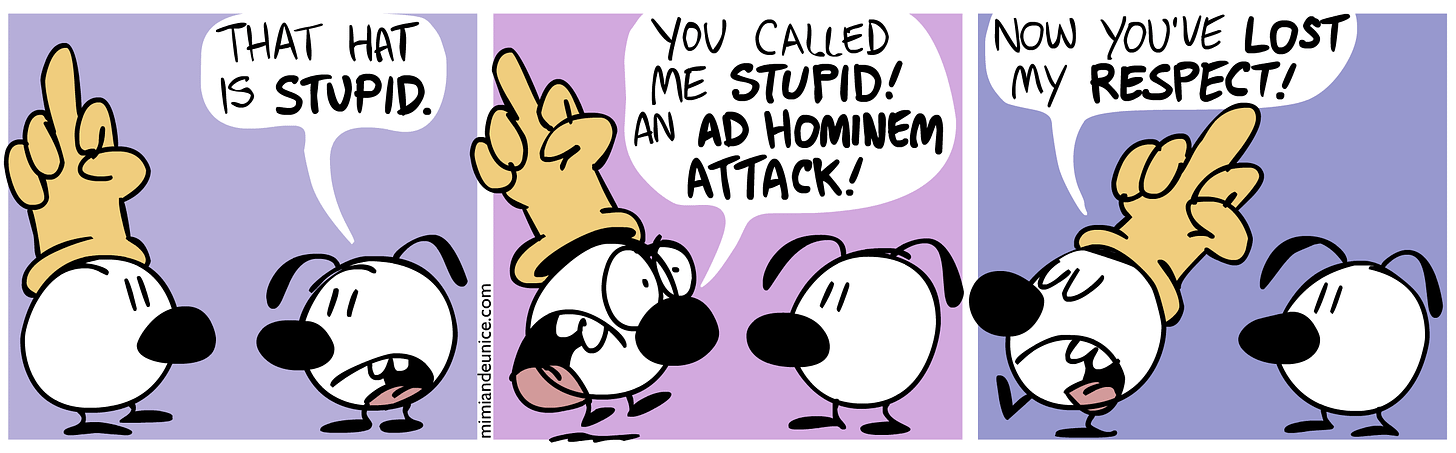

Image: “Mimi & Eunice, “Some Things Really Are Stupid”” by Nina Paley (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ME_331_StupidHat.png) (CC BY-SA 3.0).

If you have ever taken a ‘critical thinking’ class, you might be familiar with the ad hominem fallacy. It consists in the mistake to evaluate the character or credentials of a person making an argument, instead of evaluating the argument itself. Ad hominem fallacies are pervasive, in particular in politics. If Tucker Carlson or Donald Trump would make a perfectly sensible argument, it would still be decried by lefties, in the same fashion in which a good argument by Bernie Sanders or AOC is automatically discredited by many conservatives via the person making the argument. That is representative of a terrible political culture—tribalism—with detrimental effects for the public good. But that is not the issue on which I focus in the following.

Rather, I want to focus on an aspect of the ad hominem fallacy that is less recognized: how positive credentials, in particular prestige, make people positively believe in the strength of an argument or the quality of evidence. This version of the ad hominem fallacy is dangerous because it enables the possibility of a class of elites in society and science that did not receive their credentials by merit, but by conformity to power.

In the following I will focus on such prestige credentialism, that is, a form of credentialism that is defined by the prestige of an institution that bestows credentials. Much of the following primarily applies to Anglo-American countries, and other countries that possess elite education institutions that are either officially or unofficially ranked according to prestige (e.g., Harvard, Stanford, Oxford, etc.). My focus on prestige credentials does not mean that there are no other forms of ad hominem societies, that rest, for instance, on professional and vocational credentials - however, these are less harmful than prestige credentials.

Prestige credentials in science and society

Having spent most of my working life to date in and around academia (philosophy, to be exact), in both Germany and the US, I’m going to use this milieu as an example: Say you are at a conference or in a seminar and people talk about a colleague that they find particularly impressive. What you will almost invariably hear is reference to external credentials of that person, for example that:

they have published in prestigious journal xyz,

they have a PhD or postdoc from prestigious university xyz,

they work with or published with prestigious professor xyz and/or

they have won a big, prestigious grant xyz and/or a well-reputed elite scholarship.

What you usually do not hear much about is for what research this person is known for, and what you will hear even less, is whether this research is actually good or bad. Personally speaking, in my entire time in grad school, I have probably not heard once whether my ideas themselves are good or bad. Rather, I was evaluated based on whether my arguments could be published in a prestigious journal or whether I could get a prestigious job with the direction I wanted to take my research.

So, what I constantly witnessed were ad hominem evaluations of people and ideas. In Anglo-American academia the main factors for an academic career seem to be:

the prestige of the university where you earned your PhD,

the prestige of the university where you did your postdoc,

the prestige of the university with which you are subsequently affiliated,

the prestige of the journals in which you published your work, and

the prestige of the grants you received and perhaps also the prestige of any prizes, awards or scholarships that you won.

That is problematic because prestige is a socially bestowed category, not an intellectual justification of ideas or a natural categorization of competence. That means, if you refer to prestige credentials to make a case for something, you make an ad hominem argument.

But you might still think, is that ad hominem thinking not perhaps a shortcut; do the prestigious credentials according to which people and ideas are evaluated not stand for intellectual competence and justified scientific findings? To a certain degree that might be the case. But we should also consider the following option, from a critical power perspective: Social credentials, such as prestige credentials, are bestowed by powerful elite entities. Such entities might bestow prestige according to what benefits them, and not according to what is best for society or science. And if we then evaluate people or institutions based on prestige credentials, and less on real substance, there is the risk of power corruption. And unfortunately, what we witness in contemporary academia is sometimes nothing else than one giant vicious circle where one thing that is taken to be prestigious determines which other things are prestigious.1 For instance, Harvard is prestigious because its professors won prestigious prizes, publish in prestigious journals and because the university has been ranked by prestigious professors as prestigious. A journal is, in turn, prestigious because professors from prestigious universities publish there. Such vicious prestige circles could easily reflect mere power relations.

Like noble titles granted in the past, prestige is today bestowed to children of elites, scientists that forward the causes of elites most efficiently and to future members of the managerial class; people that will truthfully act according to the aims of people in power. In countries where elites and the powerful partially procreate by sending their children to elite education institutions—one might think that this and not the concentration of elite science is the purpose of these institutions—and where elites donate to universities handsomely, it is not unlikely that this form of power corruption can occur.

In case of such elite corruption through prestige credentials, you would expect the following two things to happen. First, you would expect that the paradigms in science and the humanities taught and researched at prestigious institutions are those that are most in accord with elite power. And indeed, that seems to be the case: The dominance of orthodox, neoclassical economics and analytic philosophy at Anglo-American prestigious universities seems to confirm this expectation. This class of prestige credentialed experts presents us with ex cathedra truths in the media that a liberal consensus about economics and politics is the true, ethical and scientific one. Importantly, the prestige credentialed class does not have to justify these claims with ideas or most importantly in public and fair discussion with their opponents. Rather, their claims are portrayed as true via credentials—that is the core of the ad hominem in place here.

If we consider that power elites can bestow prestige effortlessly via funding, professorships and awards, it becomes easier to grasp how they can have such a big impact on science, without ever having to explicitly dictate an agenda. For instance, the neo-liberal revolution in economics can be better understood as the concerted effort of elites to bestow awards like Nobel prizes or prestigious professorships at prestigious universities to their shield bearers without ever having to tell them what to do or without ever having to explicitly censor their opponents. Their opponents just do not receive prestige credentials. And since many opponents of neo-liberal power on the left and right side of the political spectrum are unfortunately swayed by prestige too, they are less willing or able to see how this power mechanism exerts its influence and works against them.

Second, if elite corruption through prestige credentials were the case, you would expect that the group of people most servile to and compliant with power were showered with prestige, so that they can form the managerial class. This group of compliant people will consist of those who do not question commands and just do vigorously what is expected from them by power elites. This conditioning to act according to rules and commands without questioning starts already in school. Whether you like it or not, you have to please teachers and get good grades in a plethora of subjects, in many of which you might not even be interested—nor is it ever publicly debated why we teach exactly these subjects to children and youth. You attend clubs, you learn languages and you learn to play music instruments. You collect extracurricular activities to please schools and future employers, while none of these activities might make you better at your job nor might they help developing your character. But to enter a prestigious school, this mindless busywork is required. And it goes into overdrive in college, where further prestigious distinctions can be earned.

I do not claim that the managerial class is necessarily comprised merely by people who are good at vigorously following orders by the owner class. However, we should be wary that the ad hominem honors that these people collect, both in forms of academic prestige (e.g., graduating from Harvard Business School) and business prestige (e.g., presenting power point slides 32 hours a day for McKinsey while doing handstand pushups), do not necessarily reflect competence. Indeed, these credentials could equally well reflect servility to rules that benefit the powerful.

Such mindless other pleasing has potentially detrimental effects for science and society. For example, it discriminates against those people who might be better suited to bring about positive change in society and science. While being servile to arbitrary rules works well for people who are primarily motivated by receiving external credentials and praise, it wracks havoc on people who are primarily interested in ideas and who are motivated by personal development, truth, and social progress. And while I do not want to judge people motivated by external prestige credentials too harshly, I think they might not always make the best politicians, scientists, engineers, or civil servants—or they should at least not be the only ones that hold these positions.

You might disagree with me about my admittedly rather short explanation of who succeeds in a prestige system and why they succeed. You might also disagree with me about the state of science and society to which prestige credentialism can lead. However, I still hope we can agree on two things. First, prestige credentialism rests on a problematic form of ad hominem argumentation and accordingly we should strive to make intellectual and public debates about issues rather than credentials. Second, prestige credential systems are prone to corruption. That means, even if you do not agree with my examination of how the powerful misuse prestige systems, you may be open to the idea that this form of corruption is possible, given the intrinsically insufficient nature of an ad hominem prestige credential system.

You can find plenty of examples in academic philosophy, for instance, where some of the most prestigous philosophers can make claims such as that good philosophy is done at ‘good’ universities or by ‘good’ and ‘succesful’ philosophers, without ever being called out for making circular ad hominem arguments.