As most of us have forgotten today, the period after World War II was dominated by economic policies inspired by various forms of socialism or conservatism, ranging from planning to nationalization and strong government intervention in economic activity through industrial policy.

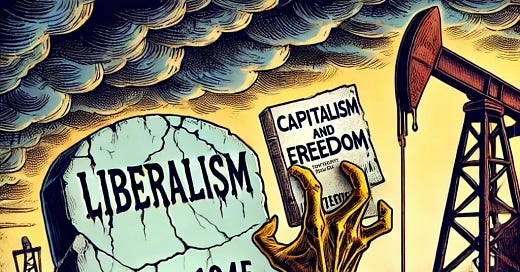

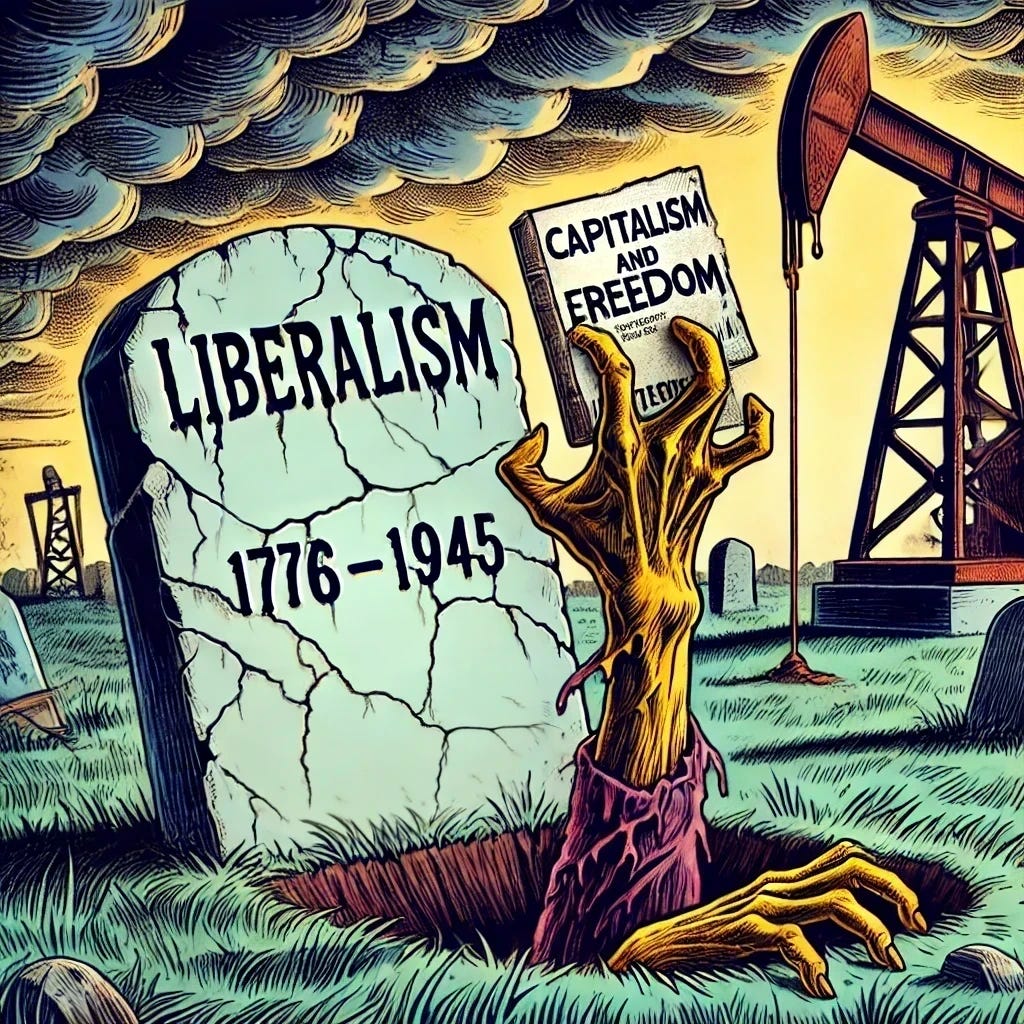

The application of these economic practices had multiple reasons. One, however, that was in everyone’s mind was the devastation that liberalism—which was rightfully associated at that time with capitalism rather than its contemporary transfiguration as the champion of freedom and justice—wrought in the 1920s and 1930s, culminating in the Great Depression, incredible poverty and mass unemployment. As Karl Polanyi states in The Great Transformation, liberalism eroded social cohesion and economic stability, weakened Western societies' resilience against external threats such as the military buildup of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, and in many ways facilitated the rise of fascism itself. All too reminiscent of our situation today.

As a result, a decisive break from liberalism and laissez-faire capitalism was the norm across Western Europe and the United States. In the United Kingdom, the Labour Party nationalized entire industries, including steel, coal, electricity and the railways system. In France, the government of conservative General Charles de Gaulle implemented state-directed economic plans (dirigisme), known as "French planning," which even the closet-liberal German chancellor Ludwig Erhard had to grudgingly acknowledge as the dominant economic paradigm of the time.

While Erhard “managed to prevent” full-scale dirigisme in Germany, the country adopted a variety of “social market economy”, a Christian-Democratic and Christian-Social model that balanced state intervention with corporate and labor union coordination. From the 1960s onward, under the socialist SPD-led government, Germany explicitly embraced Keynesian policies under economy minister Karl Schiller, which he already implemented in a coalition government with Germany’s conservative CDU. Meanwhile, in Italy, the state-run Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (IRI) played a crucial role in shaping industrial policy, economic development and functioned as a major conglomerate and employer up until the 1990s.

In the United States, the economy still profited from the re-industrialization through wartime economic planning, Roosevelt’s New Deal legacy, and a broad consensus that the government had a proactive role in economic management. Even Richard Nixon, a staunch conservative, who implemented price and wage controls, famously declared, "We are all Keynesians now," reflecting the widespread acceptance of Keynesian economic principles, which aligned with Anglo-American intellectual socialism.

And finally, in Japan, a combination of state-led industrial policy and strategic trade protections fostered rapid economic expansion, turning the country into a global manufacturing powerhouse. The Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), which guided targeted investments and technological innovation, coordinating efforts through powerful keiretsu conglomerates

The Post-War Economic Golden Age: Qualitative Mass Growth

The decades following World War II ushered in an era of unparalleled improvements in living standards—not only through rising wages but through a fundamental reshaping of economic priorities. The post-war boom was not just about income and GDP growth—though these figures were thoroughly impressive too compared to the meagre numbers of the last couple of decades—but about how prosperity was structured, distributed, and planned.

In West Germany, the Wirtschaftswunder didn’t merely restore Germany’s industrial might—it reoriented it. Industrial policy prioritized sectors that directly improved people’s daily lives: consumer goods, home appliances, affordable housing, and public infrastructure. Broad access to health insurance, robust workers’ rights through co-determination (Mitbestimmung), and strong labor unions ensured that economic gains translated into real comfort and security for ordinary Germans.

In Italy, the miracolo economico brought a wave of modernization. Industrial policies targeted consumer goods, construction, and public utilities, transforming Italy from an agrarian society into a nation of homeowners with access to modern comforts. Entire regions once marked by rural poverty were connected by highways, railways, and public services.

The United States exemplified the power of a middle-class economy shaped by industrial production. Auto manufacturing, home construction, and consumer durables like refrigerators and washing machines defined not only economic output but the American Dream itself. Crucially, strong unions and progressive taxation ensured that productivity gains flowed into middle-class prosperity.

In the UK, the results were tangible for ordinary people’s lives too. The newly created National Health Service (NHS) guaranteed universal healthcare, ending the fear of financial ruin from illness. Strong labor laws and collective bargaining rights secured better wages and safer working conditions. In France, Les Trente Glorieuses were not only years of growth but of social reconstruction. State-led planning expanded the production of affordable housing, public transportation, and utilities. Universal healthcare and expanded labor protections became pillars of a society.

And in Japan, the Japanese economic miracle was explicitly state-guided through industrial policy. The Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) steered investment toward sectors like consumer electronics and automobiles—industries that would define both the global economy and middle-class life in Japan. Meanwhile, lifetime employment systems and strong labor protections anchored the rise of a secure middle class.

Crucially, these gains were not accidental—they were planned, from “left” and “right”. Industrial policies across these countries prioritized sectors that directly heightened living standards, from home appliances to public infrastructure, from health insurance to housing. The post-war boom was a testament to the idea that economic activity should be in the service of common people—not the owners of companies.

The 1970s Oil Crises and Stagflation

The 1970s ushered in a period of economic turbulence, primarily triggered by external shocks such as the oil crises of 1973 and 1979, when the oil price increased manifold due to two different middle eastern political crises. What accompanied these crises was a steep rise in prices (inflation), which most laypeople would expect if the central form of energy used in Western countries at the time—oil—rose sharply in price.

What every layperson would also anticipate in such a situation, all things being equal, is a rise in unemployment and a reduction in economic output: if the primary energy source becomes more expensive, transport and production costs rise alike, often leading to reduced demand and subsequent job losses. That is, what economists call “stagflation”, high inflation accompanied by economic stagnation, is nothing particularly odd.

Yet, unfortunately, academic Keynesianism had developed—independent of its master himself, Keynes—in such a way that it relied increasingly on simplified “predictive” models. The most infamous of these was the Phillips curve, named after economist A.W. Phillips, which posited a stable inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment: when inflation rose, unemployment was expected to fall, and vice versa. This model suggested that policymakers could "choose" between higher inflation with low unemployment or lower inflation with higher unemployment, allowing them to balance economic objectives through fiscal and monetary policy.

However, this model, as practiced in mainstream Keynesian economics, proved inadequate when confronted with the phenomenon of stagflation—simultaneous high inflation and high unemployment—during the 1970s. According to the traditional Phillips curve interpretation, such a scenario should not have been possible. But this should not have been a devastating problem for Keynesianism either, as stagflation can be explained through external factors—such as the oil shocks of the 1970s.

Lying in Waiting: Friedman’s Sophist Moment

Milton Friedman, a founding member of the neoliberal Mont Pelerin Society, along with his colleagues, had been waiting for decades for an economic crisis to challenge Keynesian policies. He used the first oil price crisis as his ideal opening for the neoliberal assault on socialist and conservative economic policy—a push toward pre-war liberal capitalism with new emphases on financial capital and shareholder value as the primary marker of business success.

Friedman’s critique of Keynesianism was threefold. The first of these critiques is rather uncontroversial: he pointed out that the inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment did not always hold. Stagflation was empirical proof that unemployment could rise at the same time as inflation. That is indeed true. But as we said before, this is also rather unproblematic and nothing that Keynesianism—or any other sensible economic program—should have expected or depended on. A model failing to predict an event does not necessarily mean that an entire economic framework is useless—especially when that event had a plausible explanation that had little to do with the Phillips curve itself.

Yet, Friedman did not stop at this empirical refutation. Instead, he introduced two new theoretical claims himself: the concept of adaptive (rational) expectations and the claim that monetary policy is the sole variable determining inflation. Friedman argued that workers and businesses adjust their expectations based on past inflation rates. If governments attempted to lower unemployment through demand-side policies, people would quickly anticipate inflation and adjust their wage and price demands accordingly. As a result, the short-term employment gains from government spending would vanish, and unemployment would return to what Friedman called the “natural rate”—determined by structural factors rather than government policies.

This led him to the conclusion that Keynesian attempts to "manage" the economy would always fail in the long run and that monetary policy should only focus on controlling inflation rather than reducing unemployment. This, in turn, laid the intellectual foundation for the neoliberal shift of the 1980s, justifying policies that prioritized deregulation, privatization, and a reduced role of the state in the economy—ideas that became dominant with Thatcher’s and Reagan’s neoliberal capture of the conservative parties of the UK and US and still shape economic thinking today.

The Logical Problems with Friedman’s Argument

Yet, this is a bizarre development from both a theoretical and an empirical point of view. Friedman correctly pointed out that the Phillips curve was deficient. But this only disproves a specific assumption made by some Keynesian economists—it does not prove that Keynesianism as a whole is wrong, nor does it disprove other forms of state-led economic planning (whether socialist or conservative industrial policy). And most importantly, it does not prove that his own neoliberal agenda is correct. It merely shows that there is no fixed, invariant trade-off between inflation and unemployment.

Friedman’s expectations hypothesis was an ad hoc rationalization rather than a necessary conclusion from stagflation. The stagflation of the 1970s was caused by external shocks—oil price spikes—not by excessive government spending or inflationary expectations. Yet, Friedman used stagflation as evidence for a theory that it did not actually confirm.

Even more strikingly, his argument requires a nearly comical assumption: that workers and businesses kept their inflation expectations stable for three entire decades (1945–1973), despite ongoing economic expansion, wage growth, and historically low unemployment—only to suddenly and collectively adapt their expectations exactly at the moment when global oil prices skyrocketed. If inflation expectations were truly the key factor driving inflation—which also presupposes the not less tragicomic assumptions that workers and companies share Friedman’s verdict that monetary policy is sufficient for inflation and that inflation is always harmful even if it is outgrown by output and income—why didn’t they trigger a crisis at any point during the post-war boom? How is it that inflation remained moderate for decades, only to spike exactly when a global oil supply shock occurred?

Even more absurdly, Friedman’s explanation completely ignores the actual trigger of inflation in the 1970s: the oil price shock. Instead of acknowledging this obvious fact, he presupposes that inflation was caused by monetary policy. But what evidence is there that monetary policy suddenly caused inflation—precisely at the moment of a global energy crisis? This claim is not only implausible but completely unfounded—a neoliberal presupposition instead of an argument. It’s like replying to someone who claims that fluoride heightens mortality rates, that no, it is actually 5G that heightens mortality rates, and you show it at the example of someone who was just shot.

Indeed, if monetary policy were the main culprit, then why had inflation remained moderate throughout the preceding 30 years of Keynesian economic management, despite consistent government spending, industrial policies, and high employment? Why did inflation only spiral out of control when the world’s most important commodity—oil—became drastically more expensive? The answer is simple: because inflation was primarily a supply-side phenomenon, not a monetary one.

Despite decades of rapid economic growth and rising living standards, the post-war period was marked by remarkably stable prices, challenging the assumption that strong state intervention and industrial policy necessarily fuel inflation. In fact, inflation remained moderate and controlled throughout the post-war boom, even as workers gained better wages and social protections.

By contrast, from the 1980s onward—the era dominated by neoliberal policies—inflation did not disappear, despite the promises of monetarist doctrine. Friedman and his followers had built their attack on Keynesianism around the supposed inevitability of inflation under state-led economies. Yet, history tells a different story: the post-war economic order delivered both growth and stability, undermining Friedman’s narrative long before the numbers of the neoliberal era came in.

Ironically, the oil crises of the 1970s, not government spending, triggered the inflationary spike that monetarists used to discredit Keynesianism. But once the shocks passed, inflation under neoliberalism often remained comparable to the so-called “inflation-prone” post-war years—without the broad wage gains and economic security that had defined that earlier era.

Thus, rather than proving his expectations hypothesis, the actual economic history before stagflation shows that his theory was an ex post rationalization, tailored to fit a specific crisis, rather than a generalizable economic relationship description. Worse still, it was built on a convenient omission, ignoring the oil price shock.

Finally, Friedman’s refutation of the Phillips curve and his adaptive (rational) expectation hypothesis and the claim that monetary policy is the sole variable determining inflation are logically separable, they are three different statements that have no logical relationship, yet are often taken to be a conjunction, or even worse, a logical implication corresponding to a causal relationship. But that is clearly not the case. If someone claims that all cars are red, and you show that they are not, but you also claim that dragons exist, it certainly does not follow that dragons exist.

The Neoliberal Revolution and its Dire Results

The neoliberal consensus that gained massive intellectual legitimization with Friedman’s argument has ruled the Western world for the last 40 years. It started with the implementation of neoliberal policies in Chile after the coup of fascist dictator Augusto Pinochet against the elected democratic president Salvador Allende. Friedman himself went 1975 to Chile to advise Pinochet on “shock therapy”, i.e. market-radical reforms that were implemented in Chile by Friedman’s students, the so called “Chicago Boys”, which led to a decade of economic turmoil.

With the takeover of conservative parties in the US and UK by neoliberals, concretely, through Reagan and Thatcher, neoliberalism became not only a worldwide phenomenon but still has full control over most Western countries today.

From economists to liberal newspapers such as the New York Times or the Guardian to politicians ranging from all spectrums, the neoliberal status quo is touted “as without alternative”. Given the “fact checking” proclivities of these members of the professional class, this is surprising, given that history offers a clear alternative that outperformed neoliberalism in most metrics—except, of course, making the rich richer.

The neoliberal era has been marked by stagnant wages and dwindling wealth for ordinary people, contributing to mass poverty and paycheck-to-paycheck living. Protected office and manufacturing jobs have vanished, replaced by exploitative, long-hour service jobs with diminished rights. We have seen two major financial crises that were averted by Keynesian monetary policy, in that the financial industry was saved two times through central bank money that is now accounted for as public debt—Keynesianism for the rich, Friedman for the rest of us.

Despite these developments, neoliberalism still rules supreme—though Trumpism might pose a challenge to it, and sadly, only Trumpism right now. Staggeringly enough, the British “Labour” Prime Minister Keir Starmer lauded Margaret Thatcher for deregulation financial capital—an outright farcical statement.

Given neoliberalism’s catastrophic outcomes, upheld by academic research crowned with a Nobel Prize for Friedman (though the Economics Nobel was, tellingly, invented by many Mont Pelerin Society–aligned economists), we must confront a deeper question: How rational is academia—particularly economics—when policies built on such fragile intellectual grounds and disastrous empirical results still dictate global policy, perpetuating economic misery worldwide?

If you are interested in my research, please consider visiting alexjeuk.com.

© 2025 Alexander Jeuk for the text. For the image see the caption.