From Fashion to Politics: The Broad Reach of Social Distinction

How social distinction divides us and makes some of us feel superior to others

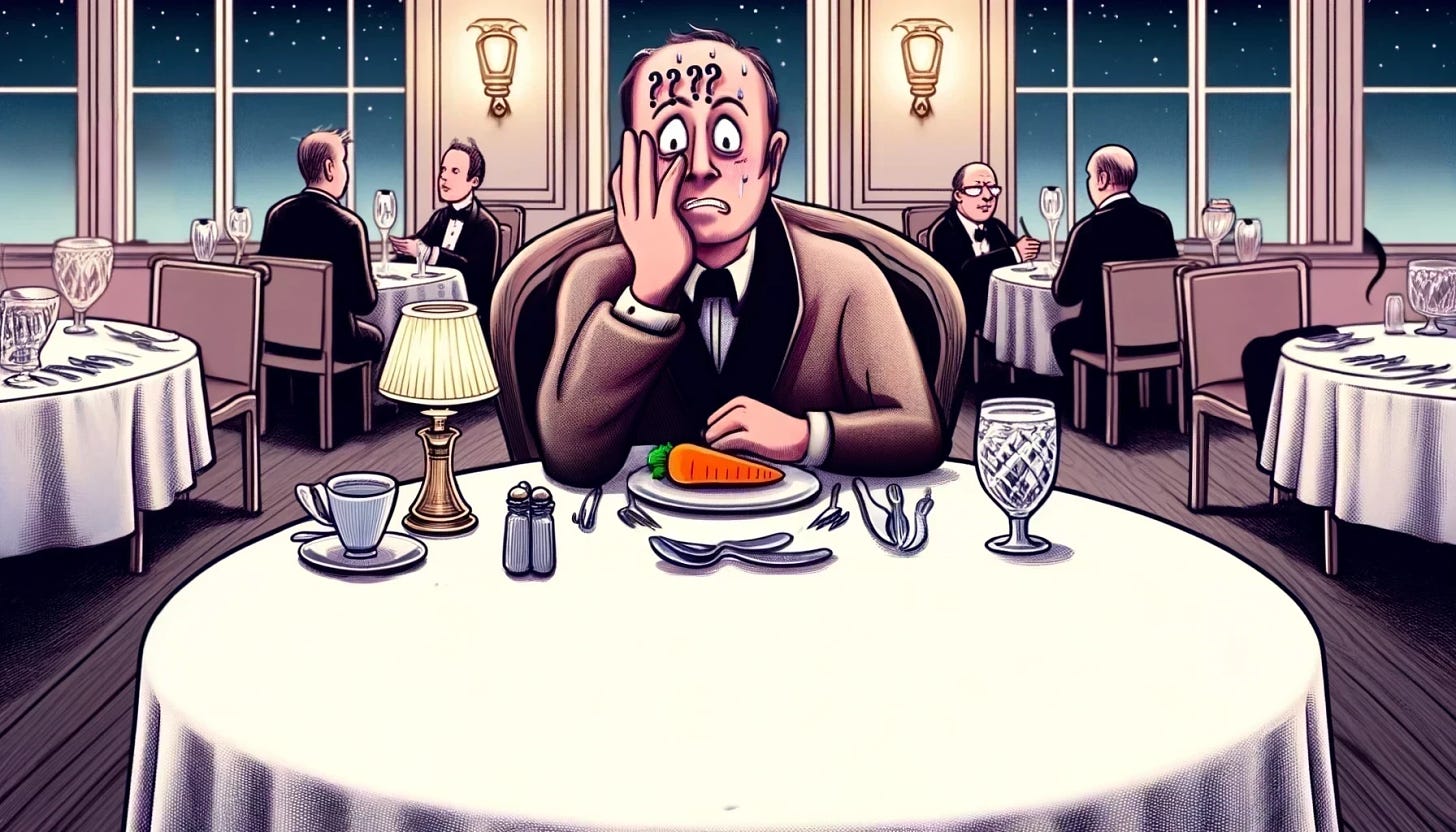

What is the purpose of this fork in this fancy restaurant? Which button on my blazer should remain unbuttoned? Which wine pairs best with fish? How long should I look at a painting in a museum? What is the appropriate attire for the opera?

These questions are not merely about innocent "etiquette" or fashion; they signify a deeper, often anxious engagement with social norms and expectations. Such concerns reflect a fear of social missteps—of not fitting in or being judged inadequate. From attire to cultural preferences, our behaviors are heavily influenced by our desire to align with, or distinguish ourselves from, others—a process that we can call social distinction.

Fellini or the Avengers? Bergman or the Pirates of the Caribbean?

Say, if you mention in a conversation that you watch movies by Bergman or Fellini and despise Hollywood films like Avengers or Pirates of the Caribbean, then this can be just that: the genuine expression of your preferences.

But in some cases, it is fair to assume that we utter such statements to socially distinguish ourselves from others; for instance, for the purpose of having the feeling that we are more refined and, in some sense, “better” than they are.

In many social settings, these choices can lead to feelings of adequacy or rejection, pride or embarrassment, superiority or inferiority. For example, consider the distinct reactions to my sky-blue sneakers and colorful chino pants. In a bigger city, this attire could signal belonging to a certain urban, perhaps avant-garde class.

Conversely, the same outfit might mark me as different in a rural area, perhaps for some as someone trying to stand out or claim superiority over the locals, independent of my intention. Indeed, when I was a child, even listening to a slightly less popular radio station, which still qualifies as completely aligned with mass popular culture, was considered by a friend as the attempt of being “better” than others.

These distinctions—as well as the counter-attempts at conformity—are not limited to fashion. They permeate various aspects of life, including music tastes, dietary preferences, literary as well as artistic education, and even political affiliations.

When social distinction becomes a problem

Of course, on one level, we might view these expressions of likes and preferences as benign personal choices, which they often are. However, they can also function as markers of social positioning, aligning individuals with specific social circles and identities.

That in itself is not problematic either per se. For many of us, it is meaningful and important to belong to a certain group. Yet, the issue becomes problematic when social distinction justifies power of some people over others, when it leads to emotional harm, and when it undermines the political process.

Contemporary art and fine dining practices to justify exclusivity?

Pierre Bourdieu is perhaps the major contributor to our thinking about social distinction. His classic example of social distinction is contemporary art. Much contemporary art is used to distinguish oneself from others who are supposedly not educated or cultured enough to appreciate it.

In that sense, contemporary art is an insider game that is not genuinely seeking to be attractive to people, as art was in the past. Rather, it is conducted and consumed by a small in-group for the sake of the opposite: social distinction.

Another important thinker on social distinction, Norbert Elias, also provided a case analysis of how socially distinctive practices, seemingly innocent as dining practices, allowed aristocrats and later members of the bourgeoisie to set themselves apart from others. That is, less “deserving”, less “cultured” parts of society, who, in the same way in which they have not read Shakespeare or Goethe, do not know how to eat out in a restaurant.

In that sense, social distinction can function as a soft power mechanism constituted by pseudo-justifications for belonging to a certain class or justifying power over people of a different class.

Importantly, contrary to Elias, and particularly Bourdieu, I do not claim that all “stylistic” choices have the purpose of social distinction. That is absurd and the relic of an explanatory ideal in the social sciences to reduce every social phenomenon to a singular cause. Often, our preferences are an expression of what we like against the confines of what we know.

The fact that we have developed so many pluralistic likes and preferences is indeed a value in itself; something at the very core of Marx’s idea of pluralistic desire satisfaction and self-realization. But in some cases, it is unfortunately social distinction at work; in particular then when it is used to exert power or misguided exclusivity over and against others.

The dire consequences of social distinction: Emotional harm

Social distinction has a significant potential for emotional harm, the perhaps most disastrous one feelings of inferiority. Huge portions of the population are constantly gaslighted into believing that they are not educated or refined enough to appreciate or understand the arts or that they lack appropriate moral judgments—usually in the absence of any adequate political or ethical public discourse.

Wounds from believing that one is uneducated, inadequate, or "stupid" can sit deep—which is even more outrageous, if we consider that a lot of (educational) social distinctive practices might just primarily have the function to make people from lower-economic strata feel terrible. And as if that is not bad enough, I believe that such emotional hurt contributes to the rising radicalization between political camps.

Social distinction in politics

On the political level, the effects of social distinction can be particularly pernicious. In some cases, political parties and movements, which historically aimed to represent broad swathes of the population, have morphed into echo chambers that serve more as markers of social identity than platforms for widespread societal change.

The case of the left: From mass movements to socially distinctive sects

In that sense, some left-wing parties have devolved into sectarian groups, which seem to choose their political agenda based on how to socially distinguish themselves from the likes and preferences of exactly those working-class people whom they were actually supposed to free from capitalism; the singular purpose of socialism and social democracy. It appears that the aim of this behavior is to allow members to feel part of an exclusive avant-garde, gaining social capital despite economically disadvantaged positions.

For everyone who is as strongly inspired as I am by Marx, Polanyi, or pre-WWII social democracy and accordingly nothing short of startled by how the left developed as it did, social distinction might be one cause worth looking at.

How to drive a wedge between people: Politicizing lifestyle choices

Likewise, the dynamics between conservatives and (social) liberals seem to consist in mutually responsive contrarianism about the likes and preferences of their base. Parties seem to focus on topics not because they rationally cohere with certain political, ethical, and economic positions, but seemingly focus on those that are best to agitate the base of the opposing camps.

That is, instead of aiming for positive societal change for all, parties have come to divide the electorate exactly around those issues that seem to drive a wedge through the working class; topics drafted around stylistic issues of social distinction that agitate people and drive the wedge deeper.

The prime example here is that of climate change. The issue is often discussed in terms of socially distinctive personal lifestyle choices (e.g., SUVs versus bikes), rather than being tackled in terms of industrial policy. This has led to the bizarre situation that environmentalism, traditionally a conservative issue, is now despised by many conservatives.

Such political procedures are, of course, aligned with the strategy of culture wars and identity politics and seem to derive from the neoliberal playbook on how to halt societal progress.

In the same way in which Bourdieu and Elias emphasized how the elites of different ages have used social distinction for their gain, it is used by neoliberals today in the context of party politics.